Algebraic geometry is not a subject that often arises in conversations around data science and machine learning. However, recent work in the field of tropical geometry (a subset of algebraic geometry) suggests that this subject might be able give some insights into the types of functions representable by neural networks (as well as give some upper bounds on the complexity of functions representable by neural nets of fixed width and depth).

As a former academic mathematician and current data scientist, I’m always somewhat surprised (but excited!) when there end up being direct connections between what I studied during my PhD and the work that I’m doing now. Because my research was in the fields of algebraic geometry and commutative algebra (neither of which is especially renowned for its connections to the real world), the opportunities to spot these links are few and far between.

That’s why the paper Tropical Geometry ofDeep Neural Networks by Zhang, Naitzat, and Lim caught my eye – in this paper, the authors give an equivalence between the functions that can be learned by deep neural networks with ReLU activation functions (a powerful but somewhat hard-to-interpret class of functions) and a class of mathematical objects known as tropical rational functions, which come from a subfield of algebraic geometry known as tropical geometry. Furthermore, the authors give some indication of how understanding the tropical geometry side of the picture could give insights into the neural networks side. While this subfield isn’t directly related to the math I worked on during my PhD, it is close enough that I was very intrigued by this paper – the most exciting situations in mathematics are those where two ideas from seemingly different areas turn out to be intimately related.

My goal for this blog post is to give enough of an idea of what algebraic and tropical geometry are about that the interested reader would feel comfortable trying to learn more, as well as sketching some of the ideas of the Zhang, Naitzat, and Lim paper.

Algebraic Geometry

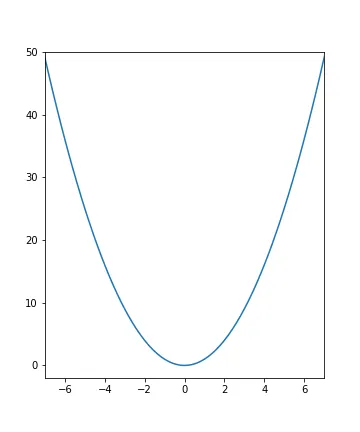

The basic idea of algebraic geometry is one that most people who have taken some math have encountered, even if they didn’t know that it was algebraic geometry at the time – given a polynomial equation (like, say, $y=x^2$), we can graph it as a function:

The main idea of algebraic geometry is that there is a very strong link between the algebraic side (the polynomial equation $y = x^2$) and the geometric side (the curve plotted in the above image), and that understanding one side of this well can give insights into the other side.

Let’s look at two more equations and their plots:

On the left is the curve $y^2 = x^3$, and on the right is the familiar circle $(x-1)^2 + y^2 = 1$, which can be rewritten as $y^2 = -x^2 – 2x$.

Just as an example of the kind of investigation one can do, we could ask the geometric question ‘given a curve, how many times can a straight line intersect it?’. Below are the same graphs with a ‘maximally intersecting’ line drawn as well.

So for the graphs of $y=x^2$ and $y^2 = -x^2 -2x$, the answer to this geometric question is $2$, while for $y^2 = x^3$, the answer is $3$. It turns out that this geometric question has an algebraic answer: it is just the degree of the polynomial (the largest power appearing on a variable). Similarly, the fact that $y=x^2$ and $y^2 = -x^2-2x$ are both ‘smooth’ at the point $(0,0)$, while $y^2=x^3$ has a ‘cusp’ at that point, is related to the lowest degree appearing in the polynomials – for the first two it is 1, while for $y^2=x^3$ it is 2.

Obviously they relationships go much deeper than those discussed above, but this is just meant to give the flavor of the kinds of problems studied in algebraic geometry.

For the interested reader, a great introduction to the basics of algebraic geometry is An Invitation to Algebraic Geometry by Smith et al.

Tropical Geometry

The basic idea of tropical geometry is to study the same kinds of questions as in standard algebraic geometry, but change what we mean when we talk about ‘polynomial equations’. In the tropical setting, we allow inputs to be from the standard real numbers plus $-infty$ (which should be thought of as shorthand for ‘a number that is less than any other number’). We then define tropical addition (denoted $oplus$) as $a oplus b = max(a,b)$, and tropical multiplication (denoted $odot$) as $a odot b = a+b$. Then a tropical polynomial is just like a standard polynomial, where usual addition and multiplication have been replaced by $oplus$ and $odot$.

For example, the tropical polynomial $1 oplus y^{odot 2} oplus (5odot x^{odot 3})$ can be rewritten in more standard notation as $max(1, 2y, 3x+5)$. The upshot of this is that now all ‘polynomial functions’ appearing in the tropical setting are maximums over collections of linear functions, which are often much more tractable to work with than usual polynomials. The true power of tropical geometry is in situations where information from this ostensibly easier-to-work-with setup can be used to answer questions about the corresponding mathematical objects in the more standard setting of algebraic geometry.

In analogy to plotting the graphs where a polynomial equation holds in the standard setting (as we did above), in the tropical setting we can plot the boundaries where the function changes between the linear terms appearing (i.e. where two of the linear terms are equal). For example, our tropical polynomial $1 oplus y^{odot 2} oplus (5odot x^{odot 3})$ is plotted below:

Note that a tropical polynomial $F$ is piecewise linear. Thus we get a partition of its domain into regions on which $F$ can be written as a single linear function. In the example above, these are the three cells split up by the lines. On the lower left rectangular region, our function equals $1$. On the top region, the function equals $2y$, and on the righthand region the function equals $3x+5$. The number of such regions is denoted by $mathcal{N}(F)$, and Zhang et al. indicate that this can be thought of as a ‘measure of complexity’ for the function $F$ – basically the more regions necessary to describe $F$, the more complicated $F$ is.

We need one more notion from tropical geometry to talk about the paper – in analogy with rational functions ($frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ where $f$ and $g$ are polynomials) in standard algebraic geometry, we can consider tropical rational functions $f(x) oslash g(x) = f(x)-g(x)$ where $f$ and $g$ are tropical polynomials. These end up being the objects that Zhang et al. show are equivalent to the functions learnable by neural networks with ReLU activation functions (with some additional mild assumptions).

For a general introduction to what tropical geometry is all about, we recommend the article What is…Tropical Geometry by Katz, along with the references therein.

Tropical Geometry of Deep Neural Networks

Now we can get to the good stuff. Zhang et al. restrict their attention to the following setup for neural networks:

- A neural network is an alternating composition of affine functions (the preactivation functions) and activation functions of the form $max(x,t)$, where ReLU is the special case where $t=0$.

- We can restrict attention to the cases where weight matrices in the activation functions are integer-valued. The idea here is that real-valued weight matrices can be arbitrarily approximated by rational-valued weight matrices, and then clearing denominators gives integer-valued weight matrices.

Then in this setting they prove that functions represented by neural networks are exactly the tropical rational functions! To do this, they proceed roughly as follows:

- First, they start with a function represented by a neural network. The first preactivation function is affine, and the first activation function is just a maximum of the output of the preactivation function and some number. We can explicitly write this as a tropical rational function.

- They then proceed inductively – given that the first $l$ layers of the neural network can be represented by a tropical rational map, they give an explicit description of the $(l+1)$st layer as a tropical rational map in terms of the weights at the $(l+1)$st layer and the tropical polynomials describing the first $l$ layers.

- For the other direction, they start by showing that tropical monomials (i.e. tropical polynomials with a single additive term) have an explicit description as a neural network in their setting, and then show that given such a description, one can derive neural network descriptions for sums and differences of tropical monomials, which then yields such a description for all tropical rational maps.

Finally, they give some applications of tropical algebraic geometry to the understanding of neural networks. The main theorem here is that the number of regions on which the tropical rational function $F$ representing a neural network is linear ($mathcal{N}(F)$) has an explicit upper bound in terms of width and depth of the neural network – in particular, it grows exponentially with the depth and linearly with the width of the neural network. Again, this can be thought of as a description of the complexity available to a neural network of fixed depth and width, with this description coming from tropical geometry!

The authors remark that this is only scratching the surface of the potential of applying tropical geometric methods to the study of neural networks. Hopefully this is the start of a long and fruitful collaboration between the two subjects.