Experimental designs such as A/B testing are a cornerstone of statistical practice. By randomly assigning treatments to subjects, we can test the effect of a test versus a control (as in a clinical trial for a proposed new drug) or can determine which of several web page layouts for a promotional offer receives the largest response. Designed, controlled experiments are a common feature of much of scientific and business research. THe internet is a natural platform from which to launch tests on almost any topic, and the principles of randomization are easily understood.

Unfortunately, not all data are collected in this manner. Observational studies are still commonplace. In medicine, many published results rely on the observation of patients as they receive care, as opposed to participating in a planned study. On the internet, offers are often sent to whitelists which are made up of non-randomly selected potential customers. And in manufacturing, it may not always be possible to control environmental variables such as temperature and humidity, or operational characteristics such as traffic intensity.

The fact that treatments are not randomly assigned should not necessarily mean that the data subsequently collected is of no use. In this note we will discuss ways that researchers can adjust their analysis to account for the way in which treatments were assigned or observed. We begin with a study of men who were admitted to hospital with suspicion of heart attack. There were 400 subjects, aged 40-70, with mortality within 30 days as the outcome. The treatment of interest in this case is whether a new therapy involving a test medication is more effective than the standard therapy. The issue is that the new therapy was not applied randomly, but rather that patient prognosis was a partial determinant in which treatment was given.

The raw data shows a lower mortality rate for the treatment group:

Outcomes of Study Alive Dead Control 168 40 Test 165 27 This corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.687, suggesting lower overall mortality for the treatment group (although a test for the hypothesis of equal mortality rates does not reject at α = 0.05). The odds ratio in this case is the ratio of the odds of death given the test relative to the odds of death given the control; values less than 1 show a stronger likelihood of survival for test subjects relative to control subjects.

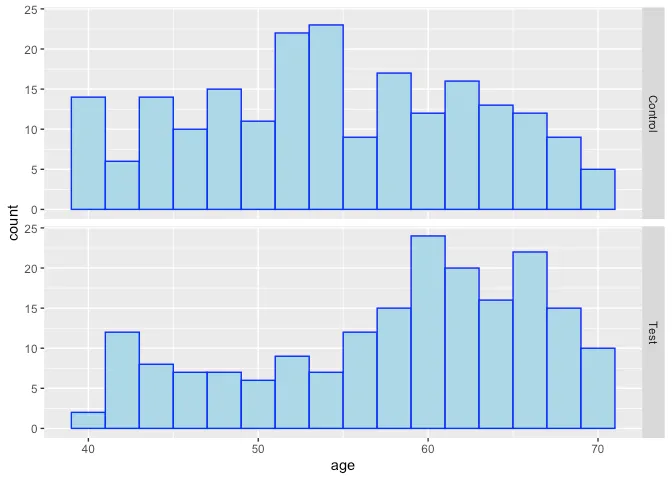

However, as suggested above, it does not appear that the treatment and control are completely similar in terms of their covariates, as might be expected in a fully randomized design – it appears that older subjects and those with higher severity scores (a clinical rating of disease severity) received the test at higher rates than the control:

Quantification of the treatment effect is at least partially confoundedwith some of the underlying conditions that correlate with increasedexpected mortality. So how to proceed?

Regression (in this case,logistic regression) is typically used to measure the effects of avariable conditional on levels of the other variables, adjusting forinequities in the distributions of the explanatory factors. Using alogistic regression in this case, with a binary variable for treatment(0 = Control, 1 = Test) and also linear variables for Age, Serverity,and Risk Score (another prognostic assessment), we find that the oddsratio for treatment vs control drops to 0.549, and is significantly lessthan 1 at α = 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval of (0.31, 0.969).However, this is an observational study, and to be useful, we need tohave more evidence that the effect of the test treatment can be measuredcleanly apart from the other variables AND from any (possiblyunintentional) selection biases that might arise due to the waytreatments were assigned to patients. That is, we need an unbiasedestimate of treatment effect, i.e., the effect of the test treatmenthave if applied to the entire population of interest. To do this, weneed to introduce the concept of a counterfactual.

Propensity Scores and Other Matching Methods

IExperimental designs such as A/B testing are a cornerstone of statistical practice. By randomly assigning treatments to subjects, we can test the effect of a test versus a control (as in a clinical trial for a proposed new drug) or can determine which of several web page layouts for a promotional offer receives the largest response. Designed, controlled experiments are a common feature of much of scientific and business research. THe internet is a natural platform from which to launch tests on almost any topic, and the principles of randomization are easily understood.

Unfortunately, not all data are collected in this manner. Observational studies are still commonplace. In medicine, many published results rely on the observation of patients as they receive care, as opposed to participating in a planned study. On the internet, offers are often sent to whitelists which are made up of non-randomly selected potential customers. And in manufacturing, it may not always be possible to control environmental variables such as temperature and humidity, or operational characteristics such as traffic intensity.

The fact that treatments are not randomly assigned should not necessarily mean that the data subsequently collected is of no use. In this note we will discuss ways that researchers can adjust their analysis to account for the way in which treatments were assigned or observed. We begin with a study of men who were admitted to hospital with suspicion of heart attack. There were 400 subjects, aged 40-70, with mortality within 30 days as the outcome. The treatment of interest in this case is whether a new therapy involving a test medication is more effective than the standard therapy. The issue is that the new therapy was not applied randomly, but rather that patient prognosis was a partial determinant in which treatment was given.

The raw data shows a lower mortality rate for the treatment group:

Outcomes of Study

Alive Dead

Control 168 40

Test 165 27

This corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.687, suggesting lower overall mortality for the treatment group (although a test for the hypothesis of equal mortality rates does not reject at α = 0.05). The odds ratio in this case is the ratio of the odds of death given the test relative to the odds of death given the control; values less than 1 show a stronger likelihood of survival for test subjects relative to control subjects.

However, as suggested above, it does not appear that the treatment and control are completely similar in terms of their covariates, as might be expected in a fully randomized design – it appears that older subjects and those with higher severity scores (a clinical rating of disease severity) received the test at higher rates than the control:

Summarizing the results, we see that all the adjustment methods givesimilar results in terms of measuring the effect of the test treatment.It is often the case that logistic regression, which produces anestimate of the conditional effect of treatment given the confoundingvariables, is very similar to the adjusted analyses that produceestimates of the marginal effect of the treatment on the population.Whenever there is interest in estimating the effects of treatments, itis recommended that a propensity-based analysis be conducted to ensurethat potential biases due to non-random design are mitigated to thehighest degree possible.

Estimates and 95% Confidence Limits for Odds Ratio of Test vs. ControlEstimateLower CIUpper CIUnadjusted0.6870.4031.171Log. Regression0.5490.3100.969Matched cases0.5110.2680.973Propensity-weighted0.5670.3011.064

Acknowledgements and Resources

This work is based on part on a modified version of an analyses by Ben

Cowling (http://web.hku.hk/~bcowling/examples/propensity.htm#thanks).

To read more about propensity scores and matching, see Dehijia and Wahba

(http://www.uh.edu/~adkugler/DehejiaWahba.pdf) and Rosenbaum and

Rubin

(http://www.stat.cmu.edu/~ryantibs/journalclub/rosenbaum_1983.pdf).

Matchit is an R package that implements many forms of matching

methods to better balance data sets

(https://gking.harvard.edu/matchit).